ACE Inhibitors and CRF Cats

|

ACEIs, especially benazepril (also known as Lotensin® and Fortekor®) and enalapril, are widely used in the UK and other Commonwealth and European countries to treat feline CRF. The promise is that the ACEI will make the cat feel more comfortable and delay the progression of the disease. Until recently, the use of benazepril or enalapril to treat feline CRF in the US was almost unknown. Recent research as to the role of proteinuria in CRF and new tests to detect trace amounts of protein in urine have led to renewed interest in ACE inhibitors, especially benazepril, as a treatment for proteinuria. Also, several US sources have reported using benazepril or enalapril prophylactically to prevent cats treated for feline hyperthyroidism with surgery or radioactive iodine from lapsing into CRF.

Benazepril and Enalapril are available in the US as generics! Many pharmacies offer "$4 a month generic" programs that include both. Wegman's sells 90 pills for $11.99. Costco Online sells 100 5-mg benazepril for $11.56 and 100 5 mg enalapril for $10.56, including shipping! Giant Foods sells 90 5-mg pills for $9.99! ThrivingPets.com sells 100 5 mg pills of benazepril for $11.95 and 100 5 mg pills of enalapril for $12.00. Important: ACE inhibitors should be given two hours apart from phosphorus binders -- the binders may interfere with absorption of the ACE inhibitors. |

Menu

Other David Jacobson Web Sites |

|

|

|

|

|

Benazepril Pills |

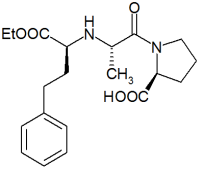

Molecular Structure of Benazepril |

Benazepril Pills |

|

|

|

|

|

Enalapril Pills |

Molecular Structure of Enalapril |

Enalapril Pills |

|

From a Novartis web site: Benazepril hydrochloride (Fortekor) is the only ACE inhibitor licensed for the treatment of CKD in cats. Fortekor has several benefits:

Due to its effect in reducing glomerular pressure, Fortekor should theoretically cause a fall in GFR. However studies have shown that GFR is maintained, probably through beneficial effects on the basement membrane leading to improved filtration efficiency.1 Read more about the benefits of Fortekor. Reference 1. S. Brown et al. (2001) Am J Vet Res, 62, 375-383. |

|

From the Vets - Articles, Books, Papers, etc: See quotes from Drs. Elizabeth Hodgkins, Dennis Chew, Steve Bartolo, James Olson and many others below: |

| From

the presentation to the July 2011 CVMA Convention, Chronic Kidney

Disease (CKD) in Dogs & Cats - The Pivotal Role of Phosphorus

Control, by Dennis J. Chew, DVM, Dipl ACVIM: Control of Proteinuria The detection of proteinuria is a diagnostic index in cats with CRF. Based on the theories of glomerular hypertension that occur in “super nephrons” of the adapted kidney, protein gaining access to tubular fluid and the mesangium is also a creator of further renal injury. The magnitude of proteinuria is a function of the integrity of the glomerular barrier, GFR, tubular reabsorptive capacity, and effects from elevated systemic and intraglomerular blood pressure. Cats with CRF increased their risk for death or euthanasia when the UPC was 0.2 to 0.4 compared to <0.2 and was further increased in cats with UPC of >0.4. The prognosis for survival is influenced by the UPC despite what has traditionally been thought to be low-level proteinuria. The effect of treatment that lower proteinuria on survival have not been specifically studied. Since even low-level proteinuria is a risk factor to not survive, it is prudent to consider treatments that lower the amount of proteinuria in those with CKD and CRF. Benazepril has been shown in two recent clinical studies to reduce the UPC in cats with CRF. Cats treated with benazepril in one study did not progress from IRIS stage 2 or 3 to the next stage as rapidly as those treated with placebo but over 6 months. Despite reduction in proteinuria in CKD cats with initial UPC > 1.0 that were treated with benazepril in another study, a significant increase in survival time was not found over placebo. |

| From a November 1, 2009 presentation to the CVC in San Diego, Updates in outpatient management of chronic kidney disease, by Cathy Langston, DVM, DACVIM: Proteinuria and antiproteinuric drugs Several studies have found that proteinuria is associated with a shorter survival time in dogs and cats with CKD. Cats with a urine protein:creatinine ratio over 0.4 had a 4 times higher risk of death than cats with a UPC < 0.2. One study found an increased risk of death in cats with a UPC between 0.2-0.4 (compared to < 0.2), but this finding was not consistent with results of another study. Significant proteinuria (UPC > 0.4) is not common in cats with CKD. About 50-66% of cats with CKD have a UPC < 0.2. Benazepril, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), decreases the magnitude of proteinuria. A randomized placebo-controlled study of almost 200 cats with CKD (Stages II-IV) did not find a survival advantage to benazepril compared to placebo when followed for 3 years. A subgroup analysis of cats with a UPC > 1 also failed to show significant difference in survival between benazepril and placebo, but included only 13 cats. In another study of 60 cats with CKD (Stages II-IV) followed for 6 months, there was no survival advantage in the benazepril group compared to placebo. There was no difference in creatinine between benazepril and placebo groups in either study. In contrast, a study of 6 cats with Stage II-III CKD treated with benazepril showed a decrease in serum creatinine (from 3.4 to 2.5 mg/dl) after 12 weeks of therapy. A similar decline in creatinine was not seen in the control group. The cats in that study had urine dipstick measurements of 2+ to 3+ without UPC measurement. I routinely monitor UPC in cats with CKD, and treat those with a UPC over 0.4 with benazepril. |

|

From the 2008 book "Caring for a cat with kidney failure" by Sarah M. A. Caney, BVSc, PhD, DSAM (Feline), MRCVS and proprietor of The Cat Professional Web Site: What about ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) inhibitors such as Fortekor® and kidney failure? In addition to the special diet and the other measures outlined above, ACE inhibitors such as benazepril (trade name Fortekor, Novartis Animal Health) have recently been advocated for the treatment of cats with kidney failure. Data from clinical trials suggests that cats receiving this therapy have a better quality of life, a better appetite, a reduction in the amount of protein they lose in their urine and may live a little longer. ACE inhibitors also lower the blood pressure and so may be prescribed as an anti-hypertensive therapy (a treatment for cats with high blood pressure). The cats that benefit most from use of an ACE inhibitor are:

Your vet should be able to advise you as to whether an ACE inhibitor is indicated in your cat. [Editor's note: Fortekor is not sold in the US but generic benazepril is readily available.] |

|

From the 2007 book "Your Cat - Simple New Secrets to a Longer, Stronger Life," by Elizabeth M. Hodgkins, DVM, Esq., former owner of the All About Cats Health & Wellness Center in Yorba Linda, CA, and nationally-known breeder of Ocicats. In the past few years, a class of drugs known as ACE inhibitors have been shown to have remarkable value in stabilizing the CRD patient. Although all of the ways in which these drugs provide this benefit are poorly understood, there is no doubt that they are helpful. The ACE inhibitor drug I like to use, benazepril, is a blood-pressure-lowering human pharmaceutical. Because a substantial number of CRD cats have high blood pressure (hypertension) as a consequence of their kidney disease, controlling high blood pressure may be one of the ways benazepril helps the feline CRD patient. ACE inhibitors may also increase blood flow to the kidneys, allowing these organs to better filter toxins from the blood. In some cats, benazepril alone does not control high blood pressure enough, and another drug called amlodipine (a different class of drug called calcium channel blockers) may be needed. Even when my patients do not have hypertension, I use benazepril in their management as I see a benefit in every patient, regardless of their blood pressure. (pages 220-221) I manage all of my CRD patients, even if they do not have high blood pressure, with the ACE inhibitor benazepril. This is because benazepril has benefits for the CRD patient that go beyond mere blood pressure control. My CRD patients take benazepril for the rest of their lives. (page 223) |

|

From "Proteinuria

and Renal Disease - A Roundtable Discussion,"

sponsored by an educational grant from IDEXX

laboratories Brown: Lees: That's the level of proteinuria at the time of renal failure. Brown: Correct. And we have antiproteinuric therapies that seem beneficial. These are interventions that can lower the magnitude of renal proteinuria. The most common are dietary protein restriction, dietary fish oil supplementation, and interventions that interfere with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. In veterinary medicine, that latter group include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, such as benazepril or enalapril. In terms of reno-protection, the interventions that are supported by studies are ACE inhibitors and dietary fish oil supplementation. In dogs, for example, there is evidence that ACE inhibitors decrease proteinuria and renal lesion magnitude concurrently. In addition, a multicenter trial that Dr. Grauer led indicated that ACE inhibitors are anti-proteinuric and potentially beneficial in spontaneous glomerular disease. Fish oil supplementation is also anti-proteinuric and renoprotectice in dogs, but there is no evidence yet of fish oil's benefits in chronic kidney disease. Ongoing clinics trials in which Dr. Sanderson is involved are evaluating the potential benefits of long-term fish oil supplementation in dogs with spontaneous chronic kidney disease -- There is reason for excitement. |

|

From Cats with Chronic Renal Failure (CRF)--How Different than CRF in Dogs? -- Paper presented at the World Small Animal Veterinary Association 32nd Annual Conference in Sydney, Australia, August 2007, by Dennis J. Chew, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medicine); Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medicine) College of Veterinary Medicine, The Ohio State University Columbus, OH, USA... click on title to read the complete paper. ACE-Inhibition and Anti-Proteinuric Treatments The detection of proteinuria is a diagnostic index in cats with CRF. Based on the theories of glomerular hypertension that occur in "super nephrons" of the adapted kidney, protein gaining access to tubular fluid and the mesangium is also a creator of further renal injury. The magnitude of proteinuria is a function of the integrity of the glomerular barrier, GFR, tubular reabsorptive capacity, and effects from elevated systemic and intraglomerular blood pressure. Cats with CRF increased their risk for death or euthanasia when the UPC was 0.2 to 0.4 compared to <0.2 and was further increased in cats with UPC of >0.4. The prognosis for survival is influenced by the UPC despite what has traditionally been thought to be low-level proteinuria. The effect of treatments that lower proteinuria on survival have not been specifically studied. Since even low-level proteinuria is a risk factor to not survive, it is prudent to consider treatments that lower the amount of proteinuria in those with CKD and CRF. Benazepril has been shown in two recent clinical studies to reduce the UPC in cats with CRF. Cats treated with benazepril in one study did not progress from IRIS stage 2 or 3 to the next stage as rapidly as those treated with placebo but over 6 months. CRF cats of another study that had a UPC of 1.0 or greater survived much longer when treated with benazepril than with placebo; no difference in survival was seen in those cats with a UPC less than 1.0. |

|

From Angiotensin Converting-Enzyme Inhibitors and the Kidney, a paper presented at the 32nd Annual World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Conference in August 2007 in Sydney, Australia (click on title to read the complete paper) by Clarke

E. Atkins, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medicine &

Cardiology) In fact, evidence is building to prove benefit when ACE-I are administered chronically to both human and veterinary patients with naturally-occurring and experimental renal failure. (14-20) Mechanisms for this improvement are postulated to be the antihypertensive effect, reduction of angiotensin II-induced mesangial cell proliferation, and renal vasodilatory effects of ACE-I, the latter related to a fall in renal filtration pressure and proteinuria. (14-16) Enalapril has recently been shown to reduce urine protein loss and reduce blood pressure in naturally-occurring canine glomerulonephritis.18 Likewise, benazepril reduced azotemia and proteinuria in a short-term study of experimental and naturally-occurring renal insufficiency in cats (19) and lowered BUN and creatinine concentrations and blood pressure in cats with polycystic kidney disease. (20) 14. Abraham PA, Opsahl JA, Halstenson CE, et al.

Efficacy and renal effects of enalapril therapy for

hypertensive patients with chronic renal

insufficiency. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:2358-2362.

|

|

From Prolonging Life and Kidney Function, a paper presented at the 32nd annual World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) in August 2007 in Sydney, Australia, by Dennis J. Chew, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medicine); Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medicine) College of Veterinary Medicine, The Ohio State University Columbus, OH, USA ACE-Inhibitors to Reduce Progression of CRF Angiotensin-II plays a pathophysiologic role in proteinuria and the progression of renal disease. It may play a role in the progression of non-proteinuric renal diseases too. Converting enzyme facilitates the generation of angiotensin-II from angiotensin-I either locally within the kidney via brush border of proximal tubules or via activity of systemic endothelium. Angiotensin-II activity within the kidney causes vasoconstriction of glomerular arterioles with a preferential effect exerted at the efferent arteriole compared to the afferent arteriole. Vasoconstriction of the efferent arteriole at a time of no change in the afferent arteriole increases intraglomerular capillary pressure. Progression of renal disease in remnant nephrons can be attributed in part to the persistence of intraglomerular hypertension, a process that is associated with increased trafficking of macromolecules into the mesangium, with resulting proliferation of mesangial cells and increased mesangial matrix (glomerulosclerosis). Angiotensin-II has nonhemodynamic effects that are potentially important since it can act as a growth factor and stimulate other growth factors that influence renal vascular and tubular growth. In a 6 month study of dogs with modest azotemia and moderate to severe proteinuria, enalapril treatment (0.5 mg/kg PO q12-24h) reduced proteinuria (as assessed by urine protein/creatinine ratio), decreased blood pressure, and slowed progression of renal disease in dogs with biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis compared to treatment with placebo. Results from this study provided enough clinical evidence to make the use of ACE-inhibition standard of care for protein-losing nephropathy in dogs caused by glomerulonephritis. Should ACE-inhibition be prescribed for dog that have tubulo-interstitial disease as the cause for their CRF? Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (e.g., enalapril, benazepril) may have protective effects in patients with chronic renal disease due to their ability to block adverse effects of angiotensin II. ACE-inhibition reduces glomerular capillary hydraulic pressure by decreasing postglomerular arteriolar resistance. Proteinuria is decreased secondary to decreased glomerular hydraulic forces and development of glomerulosclerosis is limited when protein trafficking across the glomerulus is decreased. Remnant nephrons in animals with CRF have glomerular hypertension that can benefit from reductions in transglomerular forces. An additional potential benefit from ACE-inhibition is improved control of systemic blood pressure. This beneficial effect must be balanced against their potential to worsen azotemia since glomerular pressure provides the driving force for GFR in the "super-nephron". Benazepril is licensed for treatment of CRF in cats in the European Union [Fortekor®]. Average survival of benazepril treated cats of one study was 501 days vs 391 days for placebo treated cats but this effect did achieve statistical significance. When a subset of cats in this study with proteinuria (UPC> 1.0) were considered, survival was significantly improved for those treated with benazepril (401 days in benazepril treated cats vs 126 days for control cats). Benazepril consistently reduces proteinuria in various stages of chronic kidney disease in cats and in another study stabilized cats in IRIS stage 2 and 3 more often than cats treated with placebo. |

|

From a paper presented at the 31st annual World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) in October 2006 in Prague, Czech Republic: Medical Management of Chronic Kidney Disease Scott

Brown1, VMD, PhD, DACVIM; Cathy

Brown2, VDN, PhD, DACVP; Katie Surdyk3,

DVM Staged Therapeutic Approach to CKD In the early stages of CKD, institution of treatment for any identified renal disease is a goal ("Specific Therapy"). If the identity of the disease is known (e.g., pyelonephritis), this therapy may be the critical (e.g., appropriate antibiotic therapy). Further therapeutic concerns include therapy designed to slow the progression of renal disease ("Renoprotective Therapy"), such as dietary modification (e.g., dietary omega-3 PUFA supplementation) or the use of antihypertensive agents with specific intrarenal effects (e.g., ACE inhibitors). In the latter stages, some of these complicating factors, such as electrolyte disorders and anemia are readily identified by laboratory assessment of the patient and should be treated on an individualized basis ("Symptomatic Therapy"). |

|

From a paper presented at the 31st annual World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) in October 2006 in Prague, Czech Republic: The Importance of Proteinuria and Microalbuminuria Scott

Brown1, VMD, PhD, DACVIM; Cathy

Brown2, VDN, PhD, DACVP; Katie Surdyk3,

DVM Proteinuria in Cats Once proteinuria is identified and categorized, it is critical to ascertain whether or not it is persistent. Generally, this means assessing the urine protein/creatinine ratio on 3 occasions at 2 week intervals. In cats with chronic kidney disease, urine protein/creatinine values > 0.4 in cats are associated with an increased risk of mortality. A benefit of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy has been shown for cats with a ratio of 1.0 or greater. Anti-proteinuric, renoprotective therapy is generally taken to be indicated in cats with kidney disease and a persistently elevated ratio which exceeds 0.5. In cats, this will initially be an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (e.g., benazepril at 0.5 mg/kg once daily). Results of recent studies suggest have heightened our concern about the importance of proteinuria in dogs and cats, as evidence suggests that persistent proteinuria is associated with progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and worsened mortality rates, perhaps even in animals without CKD. In veterinary medicine, we have traditionally relied upon the urine dipstick and more recently, the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, to identify and characterize proteinuria. Now there is a renewed focus on proteinuria and more specifically on microalbuminuria as a screening test for our patients. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. It has long been known that in diabetic people, proteinuria is a hallmark of impending nephropathy. Studies to quantify protein in the urine of diabetic people demonstrated that even small quantities of albuminuria were predictive of subsequent renal disease. This small amount of albuminuria (30-300 mg albumin in a 24-hour urine collection) was less than that observed in overt proteinuria (>300 mg/24 hrs) and it became known as microalbuminuria because it was a comparatively smaller ("micro") amount of albumin observed in the urine. A 24-hour urine collection test to detect for the presence microalbuminuria test has been used for decades as a screen in diabetic people. In this nomenclature, < 30mg albumin/day is normal in people, 30-300 mg/day is defined as microalbuminuria, and >300mg/day is proteinuria. While we often think of proteinuria originating from the glomerulus as a sign of kidney disease, recently it has been shown that in people with endothelial dysfunction small amounts of albumin can leak through the glomeruli of an otherwise normal kidney, producing microalbuminuria. This led to a new hypothesis: generalized endothelial dysfunction is manifest in the renal microcirculation as glomerular capillary albumin leak, which the clinician (veterinarian and physician) can detect as the presence of microalbuminuria. These consequent small amounts of albumin may be detected only by sensitive tests, which may confirm the presence of microalbuminuria. Traditionally this would require a 24-hour urine collection as a screening test. Tests for microalbuminuria became a focus in human medicine where microalbuminuria is an independent risk factor for death from cardiovascular disease and for the development of myocardial infarction and stroke in people with CKD. Indeed, these cardiovascular complications are more common end-points than uremic mortality for people with CKD. In the past decade it has become apparent that that microalbuminuria is a marker for fairly common renal and cardiovascular problems, including systemic hypertension, neoplasia, and generalized inflammatory conditions in people. As the need for a more clinically useful microalbuminuria test arose, measurement of the urine albumin/creatinine ratio (> 30 mg/gm is abnormal) or the use of albumin dipsticks became commonplace in people as a screening test for the presence of microalbuminuria. Veterinary medicine has historically utilized the routine (traditional) urine dipstick as a screening tool for identifying proteinuria and employed the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio to provide semi-quantitative information about the magnitude of proteinuria in positive cases. This back-up test is required because the dipstick is only qualitative and is fraught with problems, particularly in specificity. There is now a commercially available albumin-detecting dipstick test (E.R.D. ScreenTM Urine Test, Heska, Ft. Collins, CO) which is more sensitive and specific than the routine urine dipstick and that could be used to confirm the presence of proteinuria in the face of a positive dipstick result. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. Critically, the traditional dipstick will generally detect urine albumin present at a concentration of >30 mg/dL, whereas the new albumin-specific dipstick can reportedly detect > 1 mg/dL. Because this microalbuminuria is thus reportedly more sensitive than the traditional urine dipstick, it has been become possible to use this new dipstick as a test for the presence of microalbuminuria in dogs and cats. It can thus be employed as a screening test in dogs and cats, similar to the approach in people. By one method of classification in veterinary medicine, microalbuminuria is defined as a positive albumin-specific dipstick in the absence of a positive routine (traditional) urine dipstick. We could use this test to screen all dogs and cats for the presence of CKD or for the presence of endothelial dysfunction. Based on what we know today, we need to act cautiously in this regard as it is probably not altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. First, transient microalbuminuria may be observed in a variety of transient conditions, some of which remain to be identified in dogs and cats. Persistent microalbuminuria is an important clinical finding. In dogs and cats, persistent microalbuminuria is defined by the ACVIM Proteinuria Consensus Panel as microalbuminuria found repeatedly in > 3 specimens obtained > 2 weeks apart which cannot be attributed to a postrenal cause. Persistent microalbuminuria is often due to altered glomerular permselectivity (CKD or endothelial dysfunction); but impaired tubular handling of the small amounts of albumin that traverses the normal glomerular filtration barrier can also cause microalbuminuria. There is no clinically applicable way to reliably determine the source of microalbuminuria (glomerular vs. tubular). Nonetheless, progressive increases in magnitude of microalbuminuria are likely to indicate significant renal injury. Since persistent microalbuminuria may be a marker of either CKD or endothelial dysfunction in dogs and cats, a microalbuminuria screening test may lead to discovery of a treatable underlying CKD or an inflammatory, metabolic, or neoplastic condition in an apparently healthy animal. Urine testing that for the presence of microalbuminuria should be considered for the following circumstances: animals with chronic illnesses that may be complicated by proteinuric nephropathies (e.g., systemic lupus), screening apparently healthy dogs that are > 6 years old and cats that are > 8 years old, animals with confirmed or suspected systemic hypertension, screening dogs or cats to detect possible onset of a hereditary nephropathy as early as possible. Much remains to be learned about this exciting and novel approach that utilizes of the presence of small amounts of protein in the urine as a potentially valuable early marker of CKD and other conditions of clinical importance in dogs and cats. As veterinarians, we should be open to adopting this approach as we carefully scrutinize the literature for developing new information. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. |

|

From a paper presented at the 31st annual World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) in October 2006 in Prague, Czech Republic: Chronic Renal Failure in the Cat Andrew H. Sparkes, BvetMed, PhD, DECVIM, MRCVS ACE-inhibitor Therapy in Humans At present there is too little data available to know whether ACE-inhibitor therapy slows progression of feline CRF, although there is rationale and some data to suggest that cats with elevated (and especially markedly elevated) proteinuria levels do benefit from therapy (especially cats with a UPC ratio >1.0). If human data is applicable to the cat, then in hypertensive renal failure, the first priority is to control the hypertension, and ACEI may not adequately do this in cats. However, a second priority could be control of the degree of proteinuria and it could be argued that these two objectives might best be achieved by a combination of an ACEI and a calcium channel blocker, but evidence to support this as a first line therapy is lacking. |

|

From a paper presented at the 30th annual World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) in May 2005 in Mexico City, Mexico: Causes of Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease David F. Senior Tubulo-interstitial damage This is mounting evidence that increased traffic of plasma proteins across the glomerular capillary wall does more than damage just the glomerulus and that tubular reabsorption of excessive filtered protein plays a major role in the progression of CKD. In human patients with non-diabetic CKD, treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) reduced proteinuria and the progression renal disease and in another study the protective effect of the ACEi was more marked in those patients that had heavier proteinuria. Further, in a Heymann nephritis model of CKD in rats, simultaneous treatment of ACEi, an angiotensin receptor antagonist and a statin drug that diminishes interstitial inflammation provided the best protection. Current theories of the impact of filtered albumin and other proteins on the tubules in CKD focus on the observation that albumin upregulates tubular epithelial cell genes encoding for endothelin and a series of chemokines and cytokines that can lead to detrimental effects. Albumin is reabsorbed from the lumen of the proximal convoluted renal tubule into the apical membrane of epithelial cells by endocytosis into lysosomal vesicles. Central to subsequent processes is protein kinase C-dependent production of reactive oxygen species, nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB), and other protein kinases. NF-kappaB induces elaboration of fractalkine and other cytokines and chemokines that attract and increase adhesion for mononuclear cells, which play a role in inflammation and disease progression. No studies have been performed to confirm these mechanisms in dogs and cats but in a proteinuria model in rats, treatment with ACEi and an endothelin-A and-B receptor antagonists, proteinuria, renal lesions and NF-kappaB production was suppressed. |

|

From a paper presented at the 29th annual World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) in October 2004 in Rhodes, Greece: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Renal Failure in the Dog & Cat Hein P. Meyer, DVM, PhD, DECVIM Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) As mentioned under the etiopathogenesis of CRF, tubulo-interstitial changes are thought to play a pivotal role in the progression of renal failure from the initial insult to end-stage chronic renal failure. Thus, measures to slow the progression of these tubulo-interstitial changes potentially are of great benefit in these patients. Angiotensin II stimulates the production of several growth factors and vasoactive substances which enhance the local inflammatory response and subsequent fibrosis and sclerosis. Thus, ACE-I may inhibit these events by decreasing intrarenal ANG II concentrations. Many experimental studies in rats, and a few in dogs and cats (Brown et al 1993 and 2001) have shown a positive effect of ACE-I on the progression of CRF. Initial results of the use of the ACE-I enalapril in canine patients with CRF seem promising (Piek and Meyer, unpublished data). Apart from CRF per se, ACE-I have been proven of benefit in canine nephrotic syndrome, a specific subset of renal diseases of glomerular origin (Grauer et al, 2000) |

|

Dr. Susan Little, DVM, Diplomate of the ABVP (Feline Practice), President of the Winn Feline Foundation, co-owner of Bytown Cat Hospital and Merivale Cat Hospital in Ottawa, Canada, and Feline Internal Medicine Consultant for the Veterinary Information Network (VIN), writes in "Managing chronic diseases in cats," a 6/1/05 article in DVM360, the Newsmagazine for Veterinary Medicine: Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are receiving much attention for their role in managing cats with chronic renal insufficiency. Benazepril (0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg orally every 24 hours) improves survival time, quality of life, appetite, and weight gain in proteinuric patients with chronic renal insufficiency.13 Consider benazepril for patients with a urine protein-creatinine ratio of more than 0.4. |

|

Dec 1, 2003, DVM Newsmagazine Chronic renal insufficiency in the cat: A new look at an old disease Another study (Relation of Survival Time and Urinary Protein Excretion in Cats with Renal Failure and/or Hypertension; HM Syme) compared normal cats to those with chronic renal disease in various parameters (age, systolic blood pressure, plasma creatinine concentration, urine protein concentration, UPC). Urine protein:creatinine appeared to be a significant predictor of survival time. Median survival time for cats with UPC < 0.43 was 766 days while median survival time for cats with UPC > 0.43 was only 281 days. Interestingly, systolic blood pressure was not predictive of survival time. Proteinuria appears to be a risk factor for progression of chronic renal disease in cats and also appears to be associated with reduced survival times. Benazepril, an ACE inhibitor, appears to lower UPC and in doing so may increase survival times and slow progression of renal disease in cats. Periodic assessment of urine including a urine protein:creatinine ratio should be performed in all cats with chronic renal insufficiency. In addition, benazepril therapy should be considered along with the more conventional therapeutic regimens. Further investigation is required to determine whether reducing proteinuria with ACE inhibitors will slow the progression of renal disease and ultimately improve survival times. Potential side effects associated with long-term benazepril therapy in cats with chronic renal disease, will also need to be addressed. |

|

Home

management of cats with CRF ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) inhibitors such as benazepril (Fortekor®, Novartis): This treatment has recently been advocated based on research in people with CRF in which ACE inhibitors were found to increase the survival times. Preliminary data from a recent clinical trial in cats with CRF suggests that cats receiving this therapy have a better quality of life (as assessed by their owners) and a reduction in the amount of protein they lose in their urine. There may be a small benefit in terms of an increase in survival time, although the trials have not yet been completed and a significant increase in survival has not been proven at this stage. Fortekor did not appear to reduce the parameters used to assess renal function (e.g. blood urea and creatinine levels). However, a specific group of cats with CRF which are losing large amounts of protein in their urine do appear to show a clear response to this treatment (better survival, appetite and weight gain) although this accounts for only a small proportion of cats with CRF. ACE inhibitors also lower the blood pressure and so may be prescribed as anti-hypertensive therapy. From a longer article available on the Feline Advisory Board (UK) Web Site - see link above. |

|

From 6/27/01 presentation on Chronic Renal Failure by Steve Bartolo DVM (Ohio State University) a.

Angiotensin II and ACE inhibitors (A)

Increased efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction

relative to afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction

increases hydrostatic pressure within glomeruli and

potentially causes intraglomerular hypertension

ii. ACE inhibitors (e.g. enalapril, benazepril) may have protective effects in patients with chronic renal disease due to their ability to block adverse effects of angiotensin II listed above (A)

Reduction in proteinuria |

|

From Newman Veterinary by C. Newman DVM PHD: When using ACE inhibitors, remember that it is possible to negatively effect glomerular filtration (...azotemia...) via reduction in glomerular hydrostatic pressure which results from efferent arteriolar vasodilation. Thus, to this author a steady tendency towards elevation of BUN or creatinine after instituting treatment (even if BUN and Creatinine are in still in the normal range) should alert the clinician to consider a dose adjustment (lower). Ironically, overzealous therapy for occult renal disease could hasten development of overt renal failure! |

|

From Dr. Alan Stewart's summary notes - AAFP Atlanta Geriatric Meeting - "Old and Loving It, Feline Geriatrics into the 21st Century" Dr. Stewart also gave a presentation on hypertension. He stressed the need to identify and treat feline hypertension's underlying causes, such as renal failure or hyperthyroidism. If hypertension persists, Dr. Stewart starts treatment with a low sodium diet (K/D or H/D) and adds antihypertensive medications only if needed and with careful monitoring. He is using enalapril if the systolic pressure is less than 250mm Hg and amlodipine if the pressure is greater than 250mm Hg or if signs of hypertensive emergency—retinal detachment, cardiovascular accidents are present. If either of these drugs doesn’t control the pressure, he will add another drug to the regime rather than stop the drug and start another. Dr. Stewart has had success with adding nitroglycerin ointment, prazocin, or hydralazine. Dr. Stewart believes that controlling hypertension in renal failure cats slows the progression of the renal disease. |

|

From the Vets - Emails |

|

From Tony

Lopez, DVM, Diplomate, American Board of

Veterinary Practitioners (Canine and Feline Practice), Phillips Creek Veterinary Hospital, Sent: Fri 8/15/2008 6:43 PM I do use calcitriol and ace inhibitors routinely in both cats and dogs. The use of ace inhibitors is generally reserved for animals with renal disease that have proteinuria (protein in their urine) because that is the only group that I am aware of where we do have evidence for a beneficial effect. The proteinuria needs to be confirmed with a protein/creatinine ratio which is done on a urine sample without any other evidence of inflammation that can interfere with the results. If high, I will generally start an ace-inhibitor along with ruling out other causes of proteinuria and/or glomerulonephritis (what is likely the underlying cause of the proteinuria). I believe it is important to monitor renal function closely after starting any ace-inhibitor and continue periodic assessments. Regards, Tony |

|

From Amy Lynn, DVM, Internal Medicine Specialist, Michigan Veterinary Specialists, Southfield and Auburn Hills, Michigan: Sent: Sunday, March 16, 2008 7:58 PM As far as ace-inhibitors: Yes, I have used them in cats with CRD. The patients must be carefully selected, and close monitoring is essential to avoid potential deleterious effects. |

|

From Sarah M. A. Caney, BVSc, PhD, DSAM (Feline), MRCVS, proprietor of The Cat Professional Web Site, and author of the 2008 book "Caring for a cat with kidney failure:" Sent: Tuesday, February 19, 2008 7:14 AM Benazepril: The ACE inhibitor Benazepril has been available as a licensed treatment for renal failure in the UK (trade name Fortekor) for several years now and is commonly prescribed by UK vets. ACE inhibitors have been studied in cats since research in people with renal disease showed that those treated with an ACE inhibitor lived much longer than those that did not receive this therapy. Studies done in cats have shown a reduction in protein loss into the urine (proteinuria), a slight reduction in the blood pressure (which may or may not be enough to treat high blood pressure), improved owner reported quality of life (which is probably related to small improvements in appetite and weight gain seen with this drug) and slightly better length of life. Cats with severe proteinuria benefit the most from this drug. Benazepril does not reduce the parameters used to assess renal function (e.g. blood urea and creatinine levels). I prioritise use of this drug to cats with proteinuria (urine protein to creatinine ratio greater than 0.4, especially indicated in those cats with a ratio greater than 1.0), cats with high blood pressure (benazepril can be used alone or in combination with the more potent drug amlodipine besylate) and cats in stable renal disease whose owners wish to do everything possible for them. Renal disease is a very complex condition and there are many things that are a higher priority than ACE inhibitors as far as treatment is concerned – for example dietary management (feeding a special renal prescription diet), normalising blood phosphate and potassium levels, correcting dehydration and acidosis etc. I hope that this is of help to your website ... Thanks for getting in touch. Yours sincerely, Sarah Caney |

|

From Arnold Plotnick MS, DVM, ACVIM, ABVP (Feline Practice) and owner of Manhattan Cats Specialists in New York, NY: Sent: Tuesday, February 12, 2008 2:08 PM I’ve had more positive experiences with benazepril. To summarize the idea behind using it: some cats with CRF will excrete too much protein in their urine. Cats who lose too much protein in their urine tend to not survive as long as those with minimal urine protein loss. A recent study showed that this excessive protein loss can be reduced by giving benazepril, and that doing this improves the survival of these cats. Another study has suggested that benazepril delays the progression of chronic renal failure in all cats with CRF, not just those with excessive urine protein loss. I feel comfortable with the data that shows a benefit of using benazepril in cats with excessive urine protein loss, but I’m still waiting for more data to show an overall benefit of benazepril on all cats with CRF, regardless of their urine protein levels. So… I only prescribe benazepril if the urine protein/creatinine ratio is greater than 0.5. In the few cats I’ve given it to, the owners have reported that their cat feels great. They eat better, are more active, and have a better quality of life in general. I’m not sure why, but I’ve had enough clients tell me this that I believe it. Arnold Plotnick |

|

From Bob Vasilopulos, DVM, MS, DACVIM, Internal Medicine specialist for the Premier Veterinary Group and Internal Medicine Consultant for the Veterinary Information Network (VIN) Sent: Monday, February 11, 2008 3:58 PM The use of benazepril (and other angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors --- ACEIs) in chronic renal failure in veterinary medicine is [a] good but controversial topic. In certain instances, such as proteinuria (excessive protein in the urine) and hypertension, this treatment is well accepted -- especially since if left unchecked they can lead to further damage to the kidneys and progression of the renal failure. Otherwise, I don't routinely use ACEI in patient with chronic renal failure and probably will not routinely recommend its use until further evidence supporting its use us available. Bob Vasilopulos |

|

From Eric Zini, DVM, PhD, Dip ECVIM, Clinic for Small Animal Internal Medicine, University of Zürich Sent: Monday, February 04, 2008 2:21 AM For ACE-inhibitors, I agree, they may slow down the progression of CRF in cats. Adequate monitoring of creatinine and urea is important in order to avoid excessive doses, which may be detrimental to renal function. Eric Zini |

|

From Wendy C. Brooks, DVM, DABVP (certified in Canine and Feline Practice) and a member of the American Academy of Veterinary Dermatology, owner of the Mar Vista Animal Medical Center in Los Angeles, CA, and Educational Director, VeterinaryPartner.com: Sent: December 24, 2002 The overall feeling seems to be to remain very cautious about ACE inhibitors exc in very early CRF. ACE inhibitors reduce blood flow to the kidney which can kill nephrons. Obviously not what you want. It does seem to have benefit in reducing glomerular protein loss in early stages. Personally, my own cat went into CRF through use of an ACE inhibitor so I am not very excited about using them in any cat w/CRF. |

|

From South African Vet and Internal Medicine specialist Marlies Bohm: Wrt benazepril: I have used it in a handful of cats. Some practices I have locummed [short stay] in over the summer have used it in almost all CRF cases, some almost not at all. I haven't seen any cats get significantly worse on the drug. Some do seem to stabilise well and a few owners are really chuffed [pleased, happy] with the weight gain and improvement in appetite. So my current assessment: it seems relatively safe, but I'm not sure it helps all patients. [Email - 9/2/2002} |

|

From:

"Scott Brown" VMD, PhD, Dipl ACVIM The use of an ACEI in feline CRF is appropriate, especially early and in proteinuric cats. It is not generally reliable as sole agent therapy for hypertension but actually can be coadminstered with a calcium channel blocker in that setting (e.g., with amlodipine). [Editor's note: Dr. Brown is a member of the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine.] |

|

From: Dr. James Olson, DVM, Dipl ABVP (Feline Practice) and owner of The Cat Specialist in Castle Rock, Colorado: Sent: Monday, July 22, 2002 9:57 AM Hi David, The drug is Fortekor (Benazepril). We have seen a total reversal of Azotemia in post hypertension (I-131 treated) cats after 3 months on benazepril . . . this has been one of the big problems with hyperthyroid cats. The high blood pressure masks the kidney function and then after treatment when the blood pressure falls rapidly a small subset of these cats go into renal compromise. It appears that these cats do not have enough time to adapt to the rapid decrease in blood pressure. In humans the number one cause of renal failure is high blood pressure and this may be true in the feline. |

|

From Cat Owners - Notes concerning benazepril and enalapril. |

|

Following are emails to me from members of the Feline CRF Support Group and others.

David found your website on ACE inhibitors and CFR in cats. I see that you have reader's posts on it. If you are still updating it: My cat, Mia, was diagnosed with mid-stage CRF five years ago. She was given a year to live by the local vet. I went to see Michigan Veterinary Specialists and was given enalapril in the form of the brand Enacard (1 mg.) (unfortunately, this brand is no longer being produced). Mia is now 19 years old and in great shape with near normal BUN/Creatinine levels. My other cat Pico was diagnosed three years ago with CRF, higher than Mia's. Her counts go a slight bit up every time we take a blood sample, but it is not too bad. She is Mia's sister at 19 years. My experience is that it seems to take about eight or nine months to see improvement. There is no doubt, however, that this medication has saved their lives. Both cats have gained back most of their original weight. The vet suggested that all cats start enalapril in their older age. I would agree. I have seen absolutely no drawbacks to it. I don't know if it would work with advanced CRF, but it definitely works with mid-state CRF. Neither are on fluid or diet restriction therapy for CRF. Pico was on a very limited fluid therapy for the first few months, but it didn't seem to help so I quit it. Thank you, Ron Day From:

Phil Hampsten In case you are interested yourself or in sharing, here is an update. Sam's protein levels dropped from 15 (normal < 2.5) to 5 in three weeks of the benazepril. At this point, there are no side-effects. Her eating and drinking habits are fine. ... - Phil From:

Kim Gregory In November 2001 my 13 year old cat crashed and was subsequently diagnosed with CRF. We are in the UK and the vet was pessimistic of his chances as at that time CRF was not often treated. Ham (my cat!) had a creatinine of 400 (US 4.52 mg/dl) the vet felt that this was end stage and that the kindest option was to euthanise. Because I requested it she did agree to place him on an IV drip for 5 days. As part of his treatment he was given Fortekor – however it quickly became apparent that this was making him worse. The vet was astute enough to recognize this and stopped it immediately saying that Fortekor does make some cats worse and for some cats it plain just doesn’t help and this is especially the cats with end-stage CRf which is what she considered Ham to be. As is usual in the UK we were offered no other treatment though I did subsequently find a vet who agreed to support me with subQs. My point here is that it is recognized that cats with higher numbers often don’t do well with Fortekor and it can be dangerous to give it in these circumstances. My second experience concerns my cat Jaffa. Jaffa is now 16 and was diagnosed with mild CRF 4 and a half years ago. Jaffa was offered Fortekor by my first vet and I declined explaining that as yet there is no firm evidence that it helps. A subsequent UK vet insisted that it should be given citing that there was *proof* and that the evidence is all in from Novartis. I requested that he please provide this for me – he was unable to. So Jaffa has never had Fortekor and yet she has seen her numbers remain low throughout the 4.5 years. We have supported her with other means such as slippery elm bark and anti-nausea meds. Last autumn she seemed to be losing weight so we took her to a top UK feline specialist who is considered very experienced in dealing with CRf. Jaffa had her diagnosis of mild CRf confirmed and was also diagnosed as having chronic pancreatitis. We were not offered Fortekor, clearly she is doing fine without it. I understand that this specialist is not *anti* Fortekor but considers it important to ensure that it is prescribed in the *right* circumstances and this would not include cats with high numbers. Update 19th May 06: My Jaffa’s creatinine has jumped from normal to 3.8 US style in just a few months! I suspect that my recent switch to raw feeding and change in her regime to support her pancreatitis may well be implicated. My vet rang with yesterday evening with the results, one of the first things she mentioned was starting Fortekor – I repeated that I understood that that there is just no evidence as yet that it helps and in some circs can be dangerous. ... I called the feline specialist who we saw last autumn and said my vet had mentioned Fortekor – the specialist’s words were that “it's not a drug I would automatically reach for.” And then added that she only tends to use it in cases who are losing a lot of protein in the wee (proteinuria). This feline specialist is someone who is extremely well known as a CRF expert in the UK.”

I've posted about using benazepril (aka Fortekor and Lotensin) in my friend Vicki's cat, Sweetie. Sweetie did have I131, but did not start benazepril until 18 months later. She is doing much better on benazepril than she did without it. MJ

Pooter didn't have I-131, but he did have surgical total thyroidectomy in 1996. He's on synthroid. In

the six months between blood tests during which he

started Fortekor and Norvasc, his BUN went up

significantly, but not creatinine (which is

3.28). At 10 pounds, he's on 1.25 mg of

Fortekor and 0.8 mg His condition has remained essentially the same, except for a few weeks where an excess of potassium had him weakened. His restored vision is holding its own. PU/PD turned out to be diabetes-related, gone now. I've noticed no transient reactions to these drugs -- he goes to sleep right after dinner. The March 2001 AJVR had a research article which claimed Fortekor was good for kidneys. Darlene

Hi David, i currently have 3 on enalapril. Miss Mouse was first diagnosed with high blood pressure last summer. bp approx 220 !!. we started enalapril. this was at her yearly exam so bloodwork was done - kidney values were just fine - usg was 1.05 or 1.06. we re-tested bp one week later -- bp 215. at this point we did a t4 -- she has hyperthyroid. so we kept enalapril dose as is and added tapazole. we re-tested one week later. t4 was lowered and bp had come down to approx. 180. so, we found out she was hyper t after starting enalapril to control her high blood pressure - please note bp did NOT budge until we found the cause (hyper t) and starting correcting it. she felt SO MUCH better after starting enalapril and tapazole. she was VERY cranky before - i thought it was her personality. NO - now she's such the happy camper. we did do I-131 in January. she feels even better since going off the tapazole. kidney values and usg remain "GREAT" -- she is hypO t at the moment. L.G.

is my crf'r (diagnosed Sept 1999) with BUN 158 creat

7.4. he's also FIV+. we discovered his high blood

pressure shortly after crf diagnosis. he went on

enalapril about 1 month after his crash. his energy level **soared** with 36 hours of starting enalapril - he was dashing down the hallways!! a VERY happy kitty. his kidney values have remained essentially the same upon starting enalapril. Miles was diagnosed with high blood pressure this past spring. he is not CRF, or hyper t nor is he diabetic. as best we can tell he has primary hypertension. my vet feels that about 10% of cats with high bp are primary hypertension. enalapril has been very good for him also. he PLAYS and PLAYS - he **used** to be so "lamed back". not with enalapril. any cat at my house that is especially lazy will be tested for bp - no matter what age. enalapril has helped my crew greatly! (i have 4 others - not currently on enalapril...) Marie

Hello,

We live in Canada and it seems that it is being prescribed here. Don't know if this is why Felina has been doing so well (knock wood) but it certainly hasn't done her any harm. Barb

and Felina David, Felina gets 75-100ml [fluids] e.o.d. Tumil-k twice a day. Pet tinnic once a day and Vit b-12 per I.V. every 2 weeks. She eats Walthams low protein wet and k/d dry. Barb

and Felina Hello David Ahh it's the old Fortekor fight again. I just wanted to reaffirm my belief that Fortekor has helped Felina in the past year. She has been on it since Oct/2001 when she was diagnosed. This was 4 months after she had I-131 treatment for hyperthyrodism so I find what the Colorado Vet said quite interesting. She had a rough time in Nov/Dec that year but since January of 2002 her appetite perked up to where she has put on over 3 lbs. I have no real proof the Fortekor is what has given Felina a relatively good year. Perhaps she is just luckier than most. All I know is it hasn't done any harm.

David, Hi Sorry, meant to reply sooner to your recent post about experiences with Fortekor, but got side tracked with work! Rocky is not Hyper-T. but he is diabetic. Started Fortekor. Kidney values were relatively stable, Creat. was mid 300's. Noticed all diabetic regulation had been lost in the first 2 weeks. Tried to re-regulate him. Kept on with the Fortekor, had more bloodwork, creatinine had increased by the highest amount in a year. Stopped Fortekor after about 7 weeks. Were able to re-regulate him. Less P/U meant better hydration and the fluids seemed to have better effect. More bloodwork showed Creat still high (now at 459 from 359) but not increasing so fast. BUN was down, probably due to better hydration. Even our vet could find no reason why he suddenly became almost insulin resistant. But another UK friend using Fortekor for her diabetic cat saw the same thing happen. Vet was going to contact Novartis to make the point that perhaps Fortekor is contraindicated for some diabetics. All the best Cheryl |

|

On the Web:

|

|

Benazepril Dosage for Felines Per Novartis In

cats, FORTEKOR (aka benazepril, Lotensin) should be

administered orally at a dose of 0.5-1.0 mg

benazepril hydrochloride/kg body weight once daily

according to the following table:

FORTEKOR should be given orally once daily, with or without food. The duration of treatment is unlimited. The dose may be doubled, still administered once daily, if judged clinically necessary and advised by the veterinary surgeon. For more information, see Novartis' FORTEKOR page. Please note that the recommended oral dose for dogs is .25-0.5mg/kg body weight daily. |

|

This web site is a product of me, David Jacobson. Its purpose is to make information on using ACE inhibitors as a treatment for CRF readily available to cat owners and veterinarians. Please email me with your comments, criticisms and suggestions. |

This

site presents the available research, web links, and

veterinarian and cat owner comments on the use of

ACE Inhibitors (ACEIs) in treating cats with chronic

renal failure (CRF).

This

site presents the available research, web links, and

veterinarian and cat owner comments on the use of

ACE Inhibitors (ACEIs) in treating cats with chronic

renal failure (CRF). Critics suggest

that the research to support the use of ACEIs for

feline CRF is very preliminary, that clinical trials

are incomplete, and that they are withholding

judgment until more definitive proof is

available. They also note that ACEIs reduce

the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) through the

kidney and may actually worsen CRF. Proponents

can point to recent studies in both humans and

animals that show substantial reno-protective

benefits from ACEI treatment.

Critics suggest

that the research to support the use of ACEIs for

feline CRF is very preliminary, that clinical trials

are incomplete, and that they are withholding

judgment until more definitive proof is

available. They also note that ACEIs reduce

the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) through the

kidney and may actually worsen CRF. Proponents

can point to recent studies in both humans and

animals that show substantial reno-protective

benefits from ACEI treatment.